|

Ahmad Al-Sati |

|

|

| To read more insights from Ahmad Al-Sati, we invite you to visit his LinkedIn here.

Although the human diet can include up to 50,000 plant species, only a few dominate global agriculture, with wheat, soy, and maize being central not only to direct human consumption but also to livestock feed and industrial applications. Together, these crops make up a significant portion of global caloric intake and are essential to global food security.

However, modern agriculture’s reliance on climate predictability and resilient supply chains is increasingly under threat. Extreme weather events and unpredictable rainfall are becoming more frequent and intense, with one study projecting that crop failures will be 4.5 times higher by 2030 and up to 25 times higher by 2050. Wheat failures may occur every other year by mid-century, with even greater volatility expected for soy and maize. The Woodwell Climate Research Center forecasts that a simultaneous failure across all three crops could occur once every 11 years.

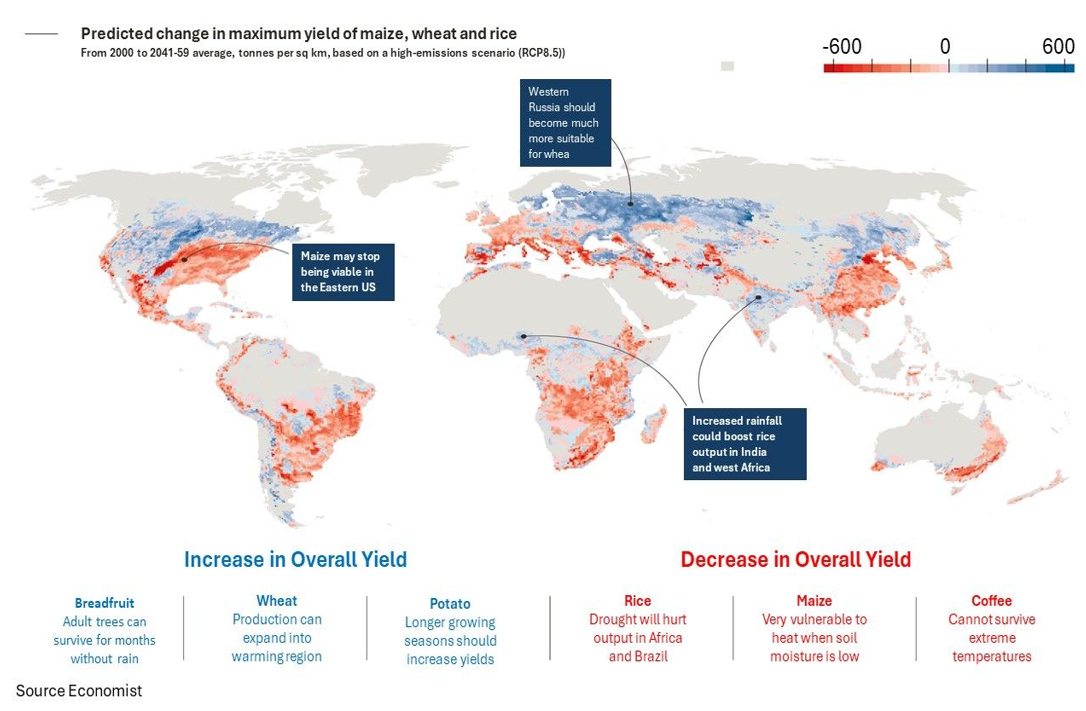

The trajectory of wheat, soy, and maize production will depend heavily on how effectively we can adapt to climate disruption. These crops are particularly vulnerable to extreme conditions. Wheat and maize yields decrease sharply during droughts—by 20.6% and 39.3%, respectively. Maize is especially sensitive to heat, with yields dropping by 1.5 bushels per acre for each day above 95°F during crucial pollination stages. While soybeans are less affected by drier conditions, they are increasingly reliant on irrigation, especially in regions with less predictable rainfall.

Geographic shifts in productivity are already occurring. Rising temperatures and changing frost patterns are expanding growing seasons across nearly every U.S. state, pushing production zones further north. Southeastern Canada may soon rival the U.S. Midwest for wheat production, while parts of the Corn Belt could see diminished productivity due to heat stress. Soybean cultivation will also shift as precipitation patterns evolve, with increased dependence on irrigation.

These changes present both challenges and opportunities for innovation and investment. Farmers will need capital to hedge against weather volatility through futures and derivatives, invest in drought-resistant seed technologies, and upgrade irrigation and transportation systems. As climate shocks become more frequent, the entire agricultural supply chain—from production to processing to logistics—will become more strategic and financially critical.

Presently, in regards to American production of these commodities , the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Prospective Plantings report for 2025 projects an increase of 4.7 million acres of corn (95.3 million total), a decrease of 3.6 million acres of soybeans (83.5 million), and a slight reduction in wheat acres (45.4 million). These shifts reflect long-term trends, with corn acres rising in the western Corn Belt and Great Plains, particularly in Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Minnesota, while wheat acres continue to decline, especially in the Great Plains. States like Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio are seeing more modest changes, with Illinois set to plant 11.1 million acres of corn and Indiana 5.4 million. However, persistent drought conditions, particularly in the western Corn Belt and Great Plains, are impacting soil moisture levels and water availability, which may further influence crop yields and planting decisions, especially for water-intensive crops like corn.

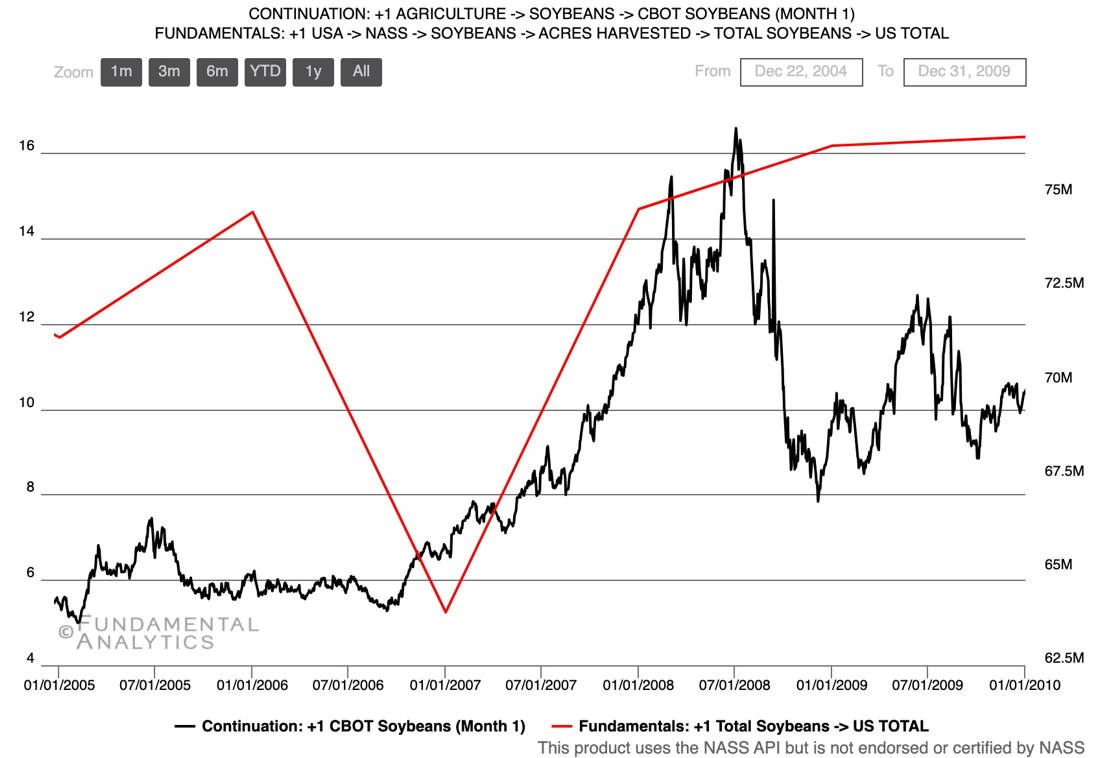

History further demonstrates the fragility of global grain markets. In 2008, droughts in key regions from previous growing seasons drove food prices sharply higher (seen in the graphic below), leading to unrest in emerging markets and bankruptcies in the U.S. agribusiness sector. |

|

|

Wheat Prices vs. Yields 2005-2010 |

|

|

Soybean Prices vs. Yields 2005-2010 |

|

|

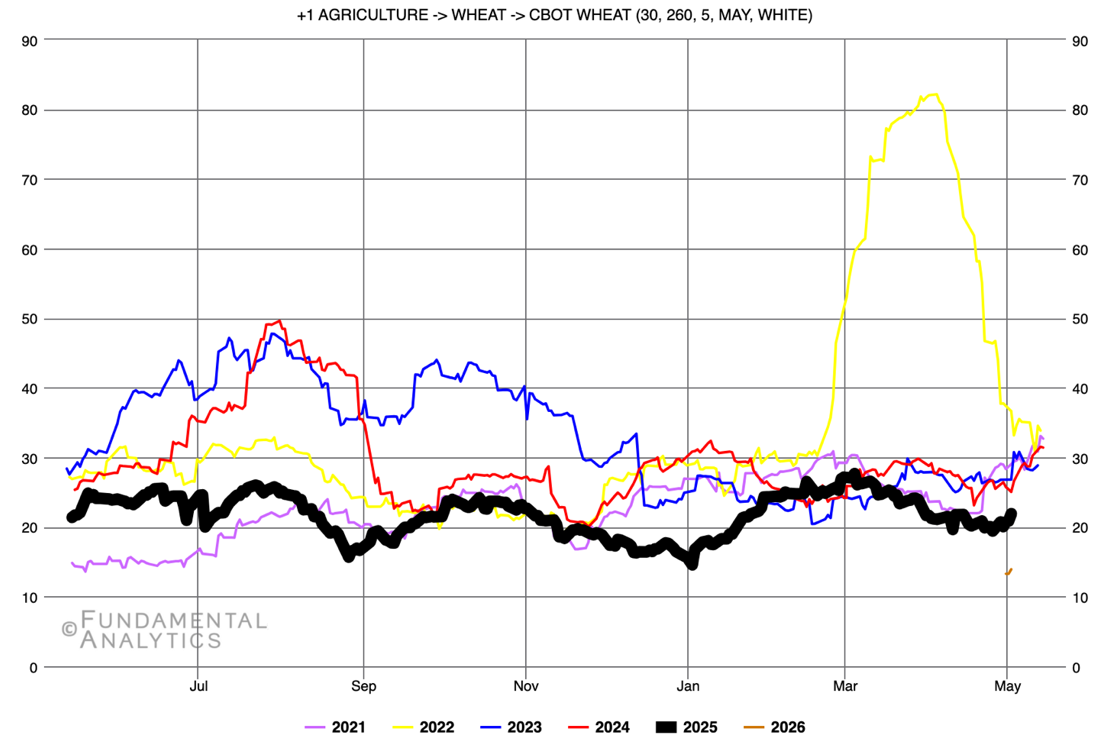

Corn Prices vs. Yields 2005-2010 In 2022, extreme drought, compounded by the Russia-Ukraine war, led to a sharp decline in wheat output and caused grain prices to rise by 6% per month on average, fueling inflation.

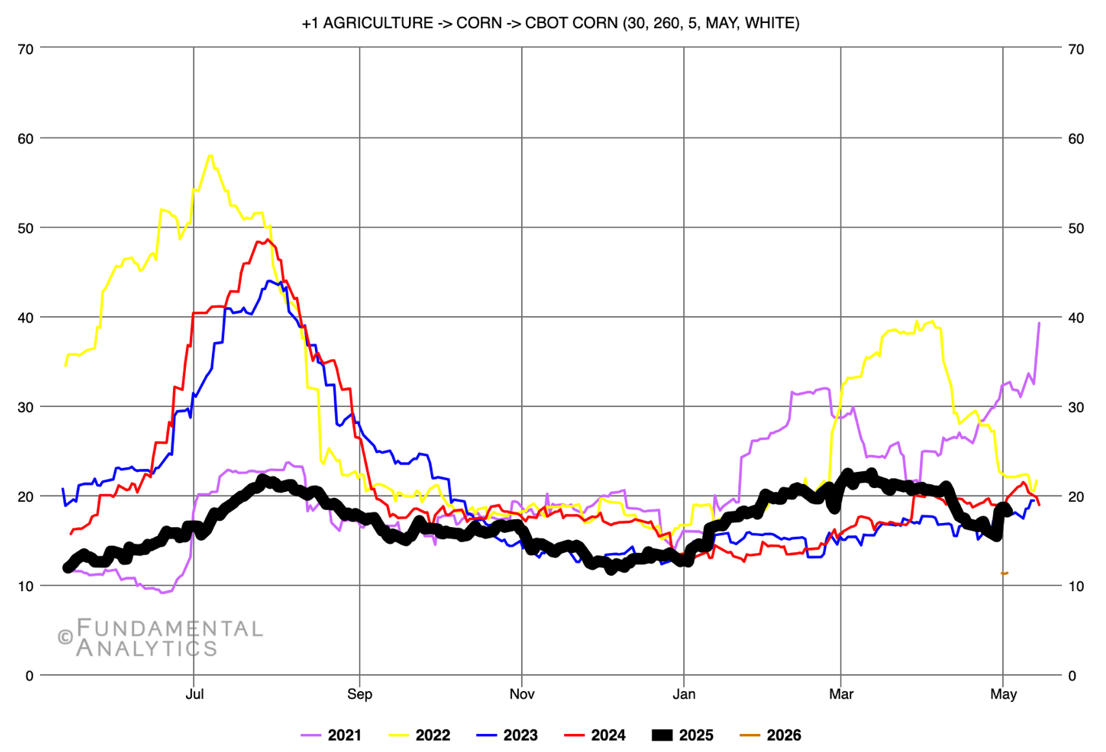

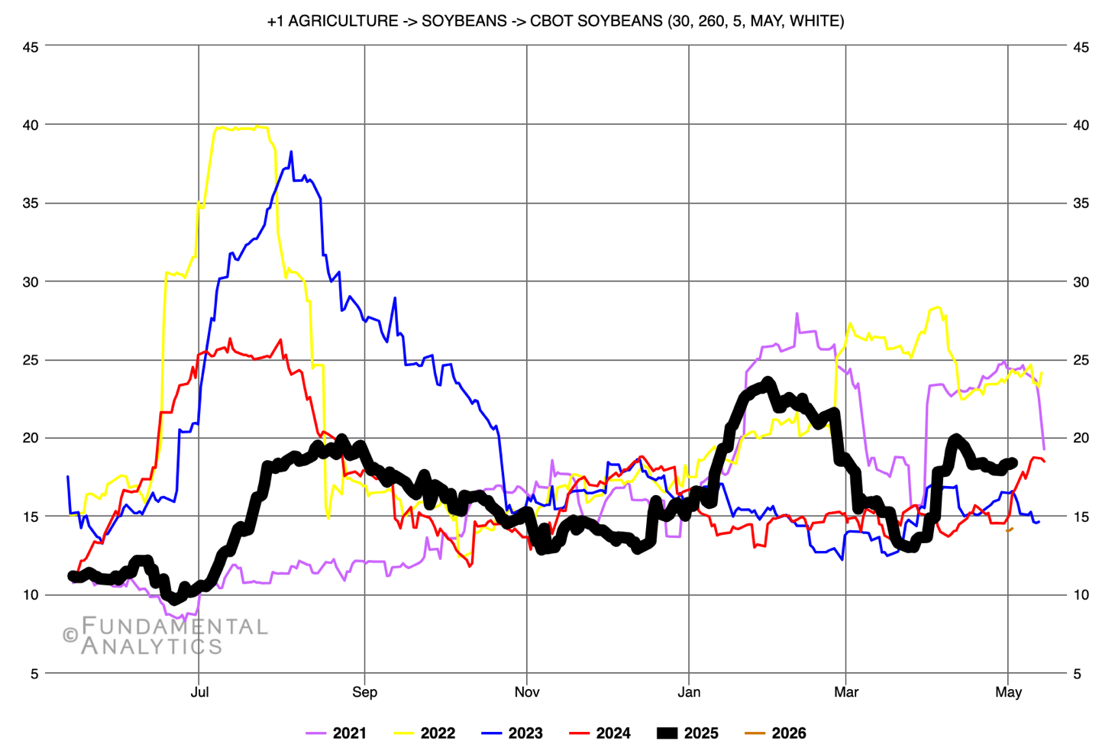

Such volatility is evident in historical CBOT price swings for corn, soy, and wheat: |

|

|

Historic Volatility of CBOT Corn Over the Last Five Years |

|

|

Historic Volatility of CBOT Soybeans Over the Last Five Years |

|

|

Historic Volatility of CBOT Wheat Over the Last Five Years Looking ahead, wheat, soy, and maize are at the center of the climate-food-finance nexus. Their future remains uncertain but holds immense potential for those who can navigate the challenges and capitalize on opportunities. Investors who understand agricultural adaptation dynamics will find growing demand for capital and innovation in this vital and rapidly evolving sector. |

|